The Opposite of Hate

Answering God’s call to peace

At the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, the 1960 presidential debates play in a continuous loop. In one of the debates, the moderator asks the presidential candidates to explain why Americans should cast a vote in their favor.

Modern viewers recognize it as a predictable moment in a debate—the point when John Kennedy and Richard Nixon will go for the jugular, degrade each other and enumerate each other’s vile traits, past indiscretions and/or gross incompetence. But that’s not what happens.

Instead, both candidates say something like this: “The American people will have to look at my experience, compare it to my opponent’s, and make a decision.” Their responses are so genteel they could almost be borrowed from the characters in a British novel.

Six decades ago, good leaders were ashamed to expose the seamy side. It’s quaint to imagine them worried about the erosion of public confidence. Today’s leaders bicker in public like a dysfunctional family on a Dr. Phil episode, energized by the spectacle of a political brawl.

How did it come to this?

Is it possible that Americans are being played for who we are—people who enjoy a good showdown, whether it’s the drama of roller derby, the brutality of boxing or the lack of personal honor in reality TV? Is our culture this way because we like it? If so, why? Why do we like to see people debasing themselves?

In the past, we expected public figures to champion rationality and civilized conduct for everyone’s sake. Many Americans now worry that our leaders have the opposite instinct, a downward slide that empowers us to lean into bad attitudes and behaviors, to let it all hang out in public.

You see the evidence in snarky comments on talk radio, in corrosive Facebook dialogues that drive good leaders from their volunteer positions, in obscene gestures exchanged between drivers, in college fraternity parties that dissolve into gun fights, in misogynistic shootings aimed at everyone in general, and in the demeaning terms we use to describe people who don’t share our opinions. Anyone on the opposite side of an issue is not just wrong; they’re stupid, naïve, daft or evil.

Americans often seem at war with each other. Even within families, battle lines are drawn. During this period of national tribulation, I find inspiration in John F. Kennedy’s 1961 inaugural address, which reminded Americans that civility is not a sign of weakness. Too many of us still fear we’ll be overpowered if we’re too gentle.

Kennedy spoke gloriously of exploring problems that unite us rather than belaboring those that divide us. He nudged us to assume responsibility for shaping the nation. Decades later his words still summon Americans to accept God’s work as our own.

How can Christians look at today’s culture without recognizing the urgent assignment God has for us: to pray for peace and to be instruments of it?

Our best shot at changing the world starts with searching our own hearts for any form of hate—subtle or overt—that works against peace in our relationships or keeps us from seeing each other in God’s image.

We can draw strength from neighbors who are executing God’s vision of peace:

- In a poor, rural town where high school students organize and serve a holiday meal intended to connect them with senior citizens.God’s instrument of peace is a 16-year-old boy with braces. Practicing the hospitality mentioned in Hebrews 13:1-25, he shares a meal and bridges a 66-year age gap by starting a conversation with my mother, “What classes did you take when you went to school here?”

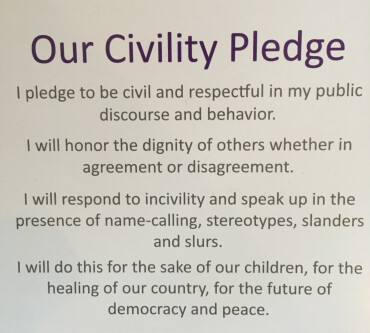

- In grassroots organizations like Women 4 Change Indiana, a group of women committed to strengthening our democracy through effective engagement in political and civil affairs.God’s change agents are Hoosier women who promote the standard of conduct described in Ephesians 4:15-16—to speak the truth in love. Their focus is: 1) to teach connective language that preserves dignity and 2) to rid conversations of hateful words that can stymy any cause. Wouldn’t it be refreshing to see this pledge widely adopted?

- In people like Sally Kohn, a well-known political commentator who converses with the authors of vicious online comments about her. Kohn wrote The Opposite of Hate, a book that dissects why and how we hate, concluding with ideas for transforming our culture. Through a gifted writer, we hear God’s exhortation to find our connectedness. Kohn reminds us of the human tendency to look for evil in others and excuse it in ourselves. If I imitate the humble tax collector who examines his own sins in Luke 18:13, could I stop dividing the world into camps?

Weary of malicious talk and hateful conduct, a mighty band of influencers is doing something about it. The Episcopal Church, the National Institute for Civil Discourse, the Jewish Council on Public Affairs, the Faith & Politics Institute, and the Public Religion Research Institute are just a few of the religious and political organizations working together to foster civil discourse and respectful dialogue.

Incivility is not just a social problem; it’s a moral one that calls Christians to action.

The Bible (and the world) is full of resources to help us respond to each other with love, especially when we don’t agree. Whether we are settling differences inside or outside the church, Christians are called to bring light into all controversial discussions. We still have so much to learn about how to disagree without turning our backs on each other.